Stroke: symptoms, consequences, and rehabilitation

The editorial staff of Emianopsia.com has the pleasure of hosting Dr Graziana Romano: graduated in psychology with a master in cognitive neuroscience. Dr Romano will guide us through a recent study on stroke.

What is a stroke?

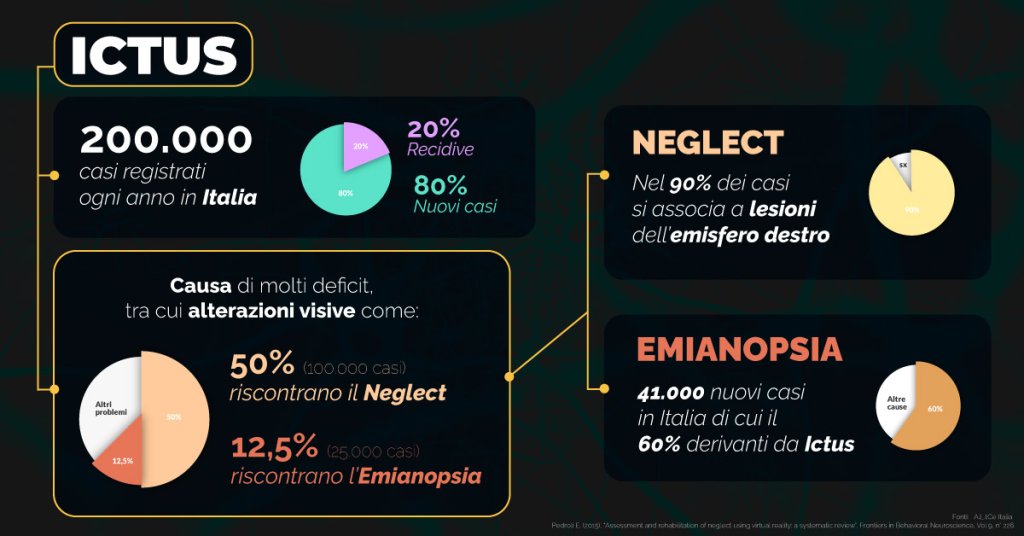

This term indicates persistent brain damage with an acute onset due to vascular causes. The WHO defined stroke as a sudden appearance of signs and symptoms related to local or global deficit (coma) of brain functions lasting more than 24 hours or with unsuccessful outcome, not attributable to another cause. Stroke represents the third cause of death in Italy, only preceded by neoplasms and cardiovascular diseases and, the major cause of disability in the adult population.

About half of the affected subjects are able to fully recover, while the other half remains affected by disabling injuries. Stroke can cause motor, sensory and cognitive deficits of varying severity; movement deficits are clearly perceived, whilst we do not know much about cognitive deficits.

Nonetheless, these deficits, can prevent an autonomous life both for the simplest activities of daily life and some complex social and relational activities. It is important to note that only 1/3 of the patients are aware that they have been affected by an acute brain event, while the remaining 2/3 do not have the same awareness (anosognosia of the disease).

How can you recognize a stroke?

The main feature of the disorder is its sudden onset; a healthy person may experience the typical symptoms that, in the following hours may be transient, remain constant, or worsen. Sometimes it is possible that some symptoms precede the stroke, such as an intense and sudden headache.

The symptoms are different in relation to the damaged area. The most frequent are:

- sudden numbness or weakness in the face, arm or leg of one half of the body;

- sudden feeling of confusion;

- difficulty in speaking and understanding what is said by others;

- sudden visual difficulty from one eye;

- difficulty in walking, often associated with dizziness and difficulty in coordination;

- severe lightning-fast headache, with no known or apparent cause;

- nausea and vomiting.

Here is a video posted by Linari Medical in which Prof. Gandolfo gives an overview of what stroke is, what its symptoms are, and what its epidemiology is.

How many kinds of strokes are there?

The brain receives blood from several arteries (blood vessels from the heart that carry blood and oxygen throughout the body), anteriorly from the two arteries called carotids (right and left) and posteriorly from the vertebral arteries, which run on both sides of the neck. A damage to any of these blood vessels present different outcomes. Cerebrovascular events can be clinically classified into four categories:

- minor ischemic or TIA:

- major ischemic;

- haemorrhagic or intraparenchymal bleeding;

- subarachnoid haemorrhage (ESA)

Overall, ischemic strokes usually occurs later in life (over 70 years), subarachnoid haemorrhages occur at a younger age (between 48 and 50 years), while intraparenchymal haemorrhages fall in an intermediate position.

Taking gender into consideration, whilst cerebral infarctions and intraparenchymal haemorrhages are more frequent in males, subarachnoid haemorrhage prevails in women.

Minor ischemic stroke or TIA

A TIA is attributable to insufficient blood supply for less than 24 hours. This type of stroke results from the temporary interruption of blood flow within the brain segments, have a rapid onset (about 5 minutes) and a short duration (from 12-15 minutes to 24 hours). They do not cause any brain trauma because they don’t damage brain cells.

In spite of this, it may be a warning sign of a forthcoming event; in fact, this kind of stroke manifests in about 1/3 of the subjects who will later present a definitive ischemic stroke and therefore represent an important factor in the identification of subjects at risk of cerebrovascular disease. The risk of stroke in individuals with TIA is more than 10 times higher than in the general population of the same age and gender.

Major ischemic stroke

This kind of stroke (80% of cases) depends on the occlusion of an intracranial vessel by means of atherosclerosis, thrombus, clots etc.).

In ischemic forms, the part of the brain supplied by the occluded vessel is no longer supplied with blood and oxygen, essential for the survival of brain tissue, which undergo cell death (necrosis), losing all function in that area, manifesting specific symptoms related to the damaged area, such as paralysis, blindness, or dizziness.

For a stroke to occur, the period of ischemia must be prolonged and persistent; on the other hand, if the duration is short and there is an immediate total recovery of brain functions, we can deem it as a transient ischemic attack (TIA).

In the case of the major embolic ischemic, a blood clot travels from the heart into the bloodstream; if it reached a small vessel, it would block the passage of blood, causing an embolic stroke. Instead, thrombotic stroke is caused by a decreased blood supply to the brain due to a fat deposit on the walls of the vessels that blocks the blood supply to one or more arteries. This definition can only be applied if symptoms last for more than 24 hours or result in death.

Haemorrhagic stroke or intraparenchymal bleeding

This type of stroke consists in the rupture of a vessel with consequent bleeding and cerebral sprain, has a higher mortality than ischemic origin’s strokes even if it only occurs in 20% of cases. In haemorrhagic forms, blood destroys a part of the brain.

Depending on the affected area, it is referred to as:

- subarachnoid haemorrhage, resulting from bleeding in the space between the inner and middle layers of the meninges, often due to trauma or rupture of a brain aneurysm;

- intracerebral haemorrhage, which is a direct bleeding within the cerebral parenchyma often attributable to chronic hypertension;

- subdural hematoma.

The classic cerebral haemorrhage is characterized by a neurological deficit that progresses in a few minutes or hours and is accompanied by headache, agitation, nausea, vomiting, increased blood pressure and seizures. The level of reduction of the state of consciousness is related to the size and location of said hematoma.

The clinical picture varies depending on the extent of the bleeding and the area affected by the brain attack.

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (ESA)

It is an acute event characterized by a haemorrhagic spread in the subarachnoid space. It is believed to be caused either by a rapid increase in intracranial pressure, or cardiac arrhythmia, or acute pulmonary edema. ESA is believed to be the only type of stroke that can cause sudden death in about 15% of cases.

What are the consequences of a stroke?

When it affects a hemisphere, it causes difficulties in the contralateral part of the body (or the contralateral part to the injury). The main cognitive disorders concern motor functions (hemiparesis), sensitive, cognitive and speech functions.

Disorders in the ability to understand and/or express, either by talking or writing, are called aphasia. Aphasia can also happen if the person is able to expresses themselves fluently but does not understand what they are told, or vice versa.

Disturbances in apraxia are manifested by the inability to voluntarily perform an action with a certain part of the body (mouth, face, legs, and arms), but still having the ability to perform that movement involuntarily.

The cognitive slowdown is a very common post-stroke disorder: most patients show a marked slowness of information processing, poor attention levels, and memory difficulties. It is likely that the person who has suffered a brain attack may develop some symptoms of vascular dementia. Quite frequently, an apoplectic stroke hitting the right parietal lobe, causes a spatial attention difficulty called neglect.

This disorder is highly disabling, considering that the person who is affected is completely unaware of everything that happens in the left half of their vision field, and very often to his own left half of the body. Other disorders of perception and recognition can be: hemianopsia, achromatopsia and anosmia for colours, visual hallucinations, agnosia.

The rehabilitation process

Depending on the severity of the lesion in the brain, the possibility of recovery of functions varies.

Rehabilitation treatment is essential and crucial, both for the recovery of movement, sensitivity, and cognitive functions and to prevent complications such as stiffness or injuries. It is always recommended to contact a stroke centre.

The purpose of the rehabilitation is to promote the patient’s learning skills, as well as developing new ones to ensure achievement of the best possible control of your body and the surrounding environment. To reach this goal, both strategies are needed to reach functional independence, despite the persistency of said deficits.

Techniques of neurorehabilitation

Rehabilitation training on neurological reorganization has implemented imaginative techniques for motor neurorehabilitation, which can be used, for instance, in individuals who show motor sensory deficits after a stroke.

Mirror therapy, for example, consists in making the hemiparetic patient move symmetrically, in a repetitive way, both upper limbs observing the healthy limb to a mirror positioned along the sagittal axis of the body to give the patient the sensation of seeing a normal motion of the paretic limb.

It is very important to carry out an accurate deficit assessment in order to build a specific rehabilitation protocol for each patient, which that considers the short and long-term objectives to be achieved.

Bibliography

- Warlow, C., Sudlow, C., Dennis, M., Wardlaw, J., & Sandercock, P. (2003). Stroke. Lancet (London, England), 362(9391), 1211–1224.

- Divani, A. A., Vazquez, G., Barrett, A. M., Asadollahi, M., & Luft, A. R. (2009). Risk factors associated with injury attributable to falling among elderly population with history of stroke. Stroke, 40(10), 3286–3292.

- Cattaneo, L., & Rizzolatti, G. (2009). The mirror neuron system. Archives of neurology, 66(5), 557–560.

- Pino, O. (2017). Ricucire i ricordi. La memoria, i suoi disturbi, le sue evidenze di efficacia dei trattamenti riabilitativi, Milano: Mondadori Education S.p.A.

You are free to reproduce this article but you must cite: emianopsia.com, title and link.

You may not use the material for commercial purposes or modify the article to create derivative works.

Read the full Creative Commons license terms at this page.